© 2025 ALLCITY Network Inc.

All rights reserved.

Zbyněk Michálek didn’t know a thing about Glendale when he arrived in Arizona via trade from the Minnesota Wild after the season-canceling 2004-05 lockout.

“Honestly, I didn’t even know anything about Arizona; I had never been here in my life,” Michálek said. “When I got here, they put me in this hotel somewhere on Bell Road in Peoria. I got to Glendale Arena and it’s in the middle of nowhere. It was farmland. I see cows and tractors running around and I’m like, ‘Am I in the right place? Is this a hockey rink or is it just some kind of agriculture building?’”

The Coyotes and owner Steve Ellman had great plans to transform that land into a destination replete with a state-of-the-art arena, shops, restaurants and residential areas. The Coyotes had played at America West Arena for six-plus seasons before moving west in December 2003. Although plans for an arena on the site of the old Los Arcos Mall in south Scottsdale had fallen through, the franchise was flush with excitement.

“There was a real sense of optimism about all of it — about the building and the development and the organization and the city and the growth of Phoenix, more specifically in Glendale. It seemed it was going to be the start of something that could be really, really special,” said NHL analyst Mike Johnson, who played his first two-plus seasons with the Coyotes at America West Arena.

“I remember we were given a pamphlet or a brochure of what the development was supposed to look like and it looked spectacular. It was this huge development of hotels and houses and restaurants and infrastructure which would lead to more residences and schools and fire departments. You imagined how great a Whiteout would be in this building, fully stocked with 18,000 people and great viewing angles and seats and amenities and everything else that was not available at America West.”

Unfortunately for the Coyotes and the City of Glendale, whose mayor, Elaine Scruggs, was trying to put her city on the map, the plans never fully materialized. The 2004-05 lockout had stalled the momentum that the Coyotes enjoyed from moving into a new arena, the rosters that the Coyotes constructed missed the playoffs in their first five full seasons in Glendale, and just after Westgate finally opened its first phase in 2007, a devastating economic recession hit in 2008 and 2009 and neither the development nor the West Valley became the next big thing that developers had envisioned.

“I remember Ellman telling people at one point that if you looked at where the population center of the Valley would be between how many people would live north and south and east and west, it was going to be somewhere right around where the arena and the Westgate development were,” said Jeff Hecht, who was director of public affairs for the Ellman Companies until 2008. “But just because people moved there didn’t make it any closer for the people in Mesa or Tempe or Chandler or Scottsdale; those loyal season-ticket holders who had supported the team when it was in downtown Phoenix and now had to drive all those extra miles. It just meant that they were really going to try to attract people from the west side and when it opened there would be a huge population center to pull from, west of the arena.

“It never developed out on the level that it was expected to and if you look at Westgate to this day, it looks very similar to what it looked like when it opened in 2007 with the exception of a few other parcels like that outlet mall they built along the freeway. The initial plans called for far more. All the parking on either the east or the west side of that main center core of Westgate was all supposed to be developed out. It was all planned to be city blocks of residential or retail or different types of entertainment or little pocket parks and none of that stuff ever really came to be as it was planned.”

Nineteen years later, the Coyotes are set to play their final game at Gila River Arena on Friday. Coincidentally, that game will come against the Nashville Predators, the same opponent that helped open the arena. Arizona will miss the playoffs for the 14th time in 18 seasons in Glendale, the team is still losing a lot of money and yet another rebuild is underway.

A list of public financial spats over the past 13 years between the city and the team led to the inevitable dissolution of their relationship. When it became clear that the Coyotes were working toward a new home in Tempe, the City of Glendale informed the team that this would be the last season of their year-to-year arena lease agreement. The team must vacate the premises by June 30 when its final payment to the city is also due.

The Coyotes are scheduled to play at least the next three seasons at Arizona State University’s 5,000-seat multi-purpose arena, but the team still does not know whether the Tempe City Council will approve its proposed arena and entertainment district on the south bank of the Salt River. As it has been since the team moved to Glendale from downtown Phoenix, uncertainty is swirling around the NHL’s most troubled franchise.

“After 19 years, I think it’s easy to say it was a mistake to put the arena out there and not put it out east,” said former Coyotes forward Ray Whitney, who now works for the NHL Department of Player Safety. “But if you look at the development and what they were thinking they were going to do and what the economy was going to do in terms of spreading out there, I think the idea was noble. I just think that the location was not thought out well enough in terms of where the hockey market is within the Valley. It’s easy to see it now, but I think it’s pretty obvious that the fans are more in the east than in the west.

“It’s a pain in the ass to get out there and if you think about it geographically, most of the money in the Valley is not out there. I hope I’m right, otherwise, why would they build another building and get going on that? They’d be better off just to move the team.”

Big plans, big risk

Former owner Richard Burke knew that the Coyotes needed a new arena. Rising payroll and the changing economics of the NHL demanded more revenue streams than the Coyotes could manage as a tenant at America West Arena. Burke thought that Los Arcos would be the perfect site. It was close to the vast majority of the team’s premium season-ticket holders, and it was close to Old Town Scottsdale and Arizona State University.

Despite initial voter and city council approval, however, the Scottsdale deal remained in limbo and property owner Steve Ellman was mulling an offer from the City of Glendale. Eventually, Burke gave in to pressure and sold the team to Ellman.

“We had a pretty complete deal to build a new stadium at Los Arcos. The stadium deal was there. The state and local tax revenue were there and I was prepared to put up the difference,” Burke said. “The piece of property was owned by someone else and it came down to the fact that those people wanted to own the team as well as build the building. In the interest of getting it done, I put it straightforwardly: ‘Either you sell me the land or I’ll sell you the team but we have to put the two together so we can get this done.’

“It’s too bad with hindsight. If it had stayed on the east side, I guess we’d probably still own the team but going where it did, it was not in the cards. I was forthright with them in saying that my personal opinion was I didn’t think it would work out there. You need to stay over here. It didn’t happen and I think all that followed was just a consequence of the economics because it wasn’t working financially. It created ownership instability regularly because of the losses in trying to find someone capable of handling those losses at the magnitude they were. A followed B.”

Hecht wasn’t certain if the Scottsdale deal was completely dead when Burke pulled the plug, but the City of Scottsdale had raised questions about Ellman’s financial capacity and the league wanted a swift resolution to the arena question.

“Even though voters had voted in favor of it and council had voted in favor of it, the local citizens just put up a huge block against it and really made it almost impossible to go forward,” Hecht said of the Scottsdale deal. “That’s when the NHL got really gung ho in saying, ‘You guys have got to work out a deal somewhere to keep it in Arizona.’ Otherwise, they were looking to pull the team out of Arizona. It may have still been possible in Scottsdale, but it would have taken a lot of time and a lot of effort and I just don’t know that there was the wherewithal to do it at that point.”

Instead, Ellman took a sweetheart deal from Glendale and had already brought hockey icon Wayne Gretzky aboard to lend credibility to the franchise as a part owner. The city agreed to pay up to $180 million in construction costs with Ellman and the Coyotes covering the rest of the $225 million price tag. When the arena finally opened two-plus months into the 2003-2004 season, the team held a huge after-party in a circus-sized tent right outside the arena. There were dignitaries, VIPs, local business people, friends, family — hundreds of people in all, and musician Kenny G played a short set.

While the team struggled, there were some memorable moments in those early years, including Brian Boucher’s record-setting shutout streak. Boucher had started the year as the team’s third-string goalie, but from Dec. 31, 2003 (four days after the Coyotes had christened their new arena) to Jan. 9, he posted five consecutive shutouts (the first at home against the Kings; the final four on the road) to set a modern-era NHL record.

“You want to talk about vindication?” Boucher, now an analyst for TNT, said, laughing. “You had this chip on your shoulder where you wanted to prove that you belonged in the net and then all of a sudden you get one, you get two, you get three and you’re like, ‘Geez, what’s happening here?’

“I think the guys got excited because they knew that I was frustrated from not being with the team and practicing. I look back on it and I’m kind of amazed that we were able to do it because we weren’t the best defensive team. We weren’t one of the top teams in the league. We were just a team that was trying to scrap and get by. It’s amazing that something like that can actually happen. In some ways it’s a bit of a miracle, especially considering the fact that I was third-string that year.”

In 2005, the first season after the lockout, Gretzky moved behind the bench as coach to strengthen his connection to the players and the game that he missed. It was a seminal moment in the history of the franchise.

“When you’re playing, there’s nothing like it,” Gretzky told reporters at the time. “You know you can go out there and affect the outcome of the game each and every night. Now the effect I can have on the game is very different, but the passion I have to help this team win is still the same I had as a player.”

Gretzky had no coaching experience, but then-azcentral.com beat writer Dave Vest, who later wrote for the team’s site, said the desire was there.

“I remember being intimidated by him simply because he was Wayne Gretzky and I was a relatively new reporter, but that faded very quickly because he never presented himself with this aura of ‘Hey, I’m Wayne Gretzky,’” Vest said. “He was very personable, he was always open to comments, he answered all of the questions and I really got that sense from him that he was taking it seriously and that he wanted to succeed right away; he wanted to become a good coach.”

Unfortunately for Gretzky, the team missed the playoffs all four seasons that he was behind the bench. One year into his coaching tenure, Ellman sold the team to Jerry Moyes, founder and CEO of Phoenix-based Swift Transportation. As the franchise’s financial losses piled up in its West Valley outpost, Moyes attempted to put the team into bankruptcy and sell it to Canadian billionaire Jim Balsillie for a relocation to Hamilton, Ontario. As that turmoil swirled around the team and the NHL eventually seized control of the franchise, Gretzky stepped down as coach and left the organization.

“I spent a lot of time with Wayne,” said former Coyotes GM Don Maloney, who was hired in May of 2007. “He’s a good man with a good heart. He just didn’t have enough time in his life to devote to what he needed to do in that job because of who he is, but his hockey mind and his stock in the game were second to none.”

A ray of hope

When Dave Tippett arrived in the midst of 2009 training camp, relocation rumors were already swirling. At one point, staff members had already been told to start searching for housing in Portland, Oregon, and over the next few seasons, various reports had the Coyotes moving to Winnipeg, Quebec, Kansas City, Houston, Las Vegas and Seattle.

“We had a practice at the Ice Den (Scottsdale) and I remember Dave Tippett came into the locker room when the Blackberry guy (Balsillie) was trying to buy the team and he said, ‘We can’t control this. Whatever happens with the ownership doesn’t matter. Let’s just do our job on the ice,’” former Coyotes center Martin Hanzal said.

“We knew about the rumors but we didn’t talk about it in the room. We just focused on playing. The biggest issue for us was driving all the way to Glendale on game days. If we had a morning skate, that meant three hours of driving each day. That’s probably why I had three back surgeries (laughs) from sitting too much in my car driving back and forth. When you do the math and think about how much time you were sitting in the car on a game day through the whole year, it’s hard.”

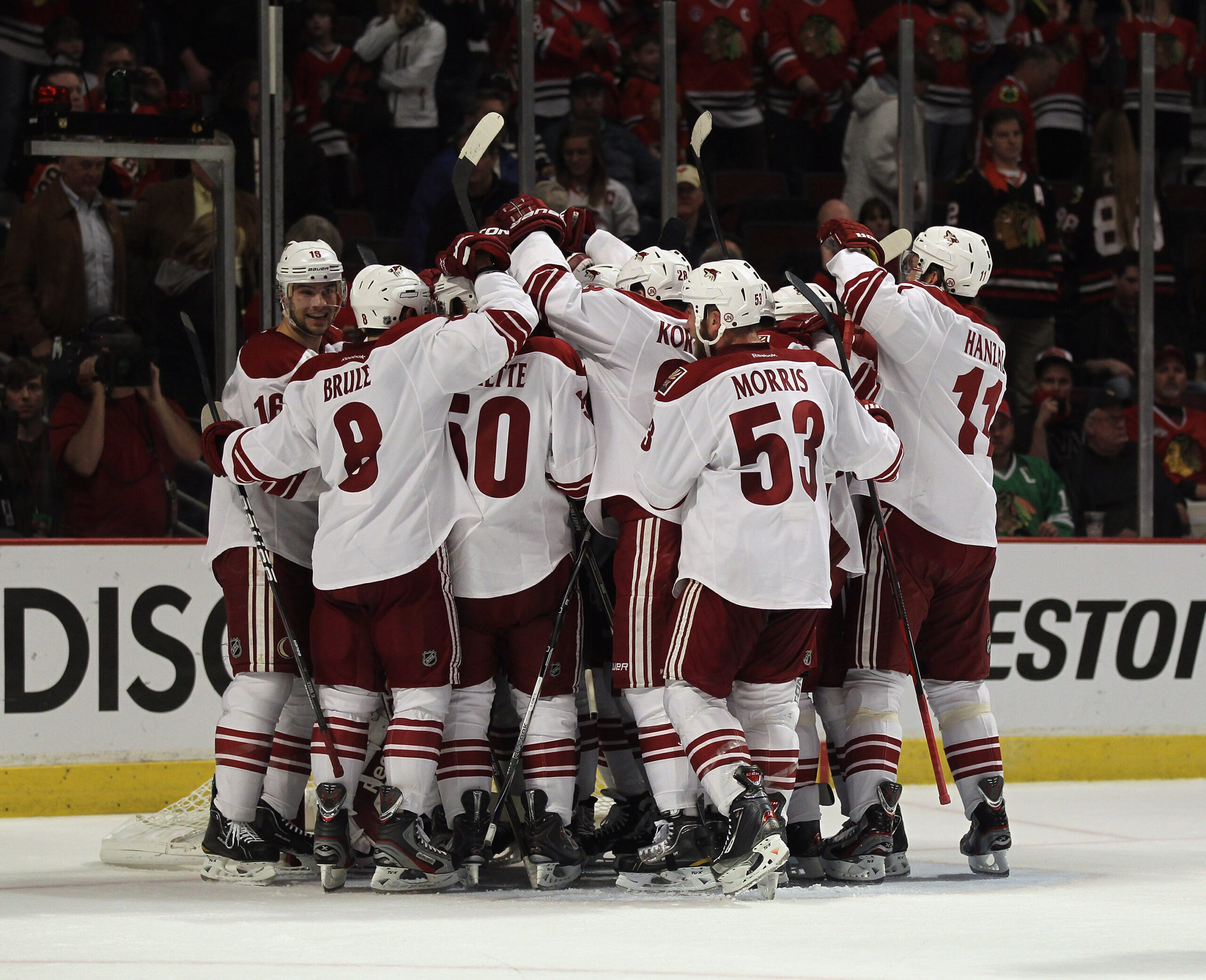

The period from 2009 to 2012 represents the best era in Coyotes hockey. Under Maloney and Tippett, and with Shane Doan serving as captain, the team made the playoffs three straight years, it established a franchise record for points (107 in 2009-10), it won its only division title (2012) and it advanced to the 2012 Western Conference Final by posting the franchise’s first two playoff series wins (Chicago and Nashville).

“I was in Spiez, Switzerland, a little town outside of Bern, when I heard that we went into bankruptcy,” Doan said. “As an organization, it was like a kick in the gut because it kind of shook everything to the core and nobody really knew what it meant for us.

“And then when Tip came into the organization, we started to galvanize with him and Don Maloney and a good group of players. When people start pointing out all the reasons that you should be bad, I think as an athlete, it gives you kind of a drive to prove people wrong and it was really strong with us. We had an all-for-one mentality and it was a lot of fun.”

None of those three playoff teams was blessed with superstars. The conference final team boasted a top line of Hanzal, Whitney and Radim Vrbata (35 goals), but in February of 2012, the team went 11-0-1 to climb out of mediocrity and into a playoff spot.

“I actually thought I was gonna get traded in February, and at one point I was actually looking forward to it because I was getting up there in age; I was turning 40 that year so I wanted another crack at it and we were a borderline team,” Whitney said. “I had a conversation with Don and said, ‘Listen, if there’s something that comes up and you have a chance to move me to a contender, go ahead.’ All of a sudden, we went unbeaten in February and with how Mike Smith was playing in goal, we ended up adding a couple players. I knew I wasn’t getting traded and at that point I didn’t want to.”

When the Coyotes clinched the Pacific Division title with a 4-1 win in Minnesota on April 7, they arrived home late, but still found a surprise waiting for them in the wee hours of Easter morning.

“When we got off the plane at the airport in Phoenix there were people waiting for us around midnight, or maybe one or two o’clock in the morning,” Vrbata said. “I think if I turned on my old phone I would still find those old videos because as we were driving by the gate, I was filming what was happening there.

“It was really exciting, it was the highlight of those teams and obviously for me, too. That was when I felt it most, the connection with the fans and the city. They were unbelievable and we really felt like we were a big part of the Valley; like we had turned a corner.”

Tippett, who retired this season, has discussed that three-year run a lot, repeatedly noting how the relocation rumors and the ownership instability galvanized the team.

“Everybody was part of the team,” he said. “It was coaches, it was trainers, it was players, it was management with Don and Brad Treliving. It was a tight-knit group, especially in those years where the NHL owned us. It was very much a galvanized group.

“What the coaches were trying to sell, the players always supported and then management tried to support that with players that fit in so it was a good chemistry and we had the momentum going the right way.”

As has often been the case with this franchise, misfortune put an end to the good times. After the conference final run, another lockout hit, finances got tighter, the sale of the team to Ice Arizona dragged on, and the 2012-13 season didn’t begin until January. Maloney offered Whitney $3 million less than the Dallas Stars offered on a two-year deal so he jumped ship, Smith suffered an injury late in the season that kept him out for two weeks and the Coyotes missed the playoffs by four points. Again, momentum was lost.

The team slipped to 89 points the following year, and a franchise-worst (for a full season) 56 points in the 2014-15 season. Maloney was fired, ownership changed hands again, this time to Andrew Barroway, and on the eve of the 2017 NHL Draft in Chicago, Tippett walked away from the team.

“I think what happened to me is what happens with so many people,” Tippett said. “You pound away at it for so long and then you just get tired. That’s where I was. The change of ownership again and again was tiring and you’re trying to work your way through it, but eventually, you run out of options.

“You’re trying to be a competitive team, but the financial realities were always at the forefront, making it difficult. That insecurity always led to question marks and the only time those question marks were taken away was by a group of players that banded together, blocked all that stuff out, had fun playing and had some success.”

When the Coyotes bottomed out in 2014-15, it was intentional. Connor McDavid and Jack Eichel were the franchise-center prizes in that draft and Maloney knew that acquiring top-tier talent was the only way to sustain success.

“I think it was harder for Tip to go that route and maybe easier for me because I just thought, ‘We have no chance, going the way we’re going. We have to reboot this thing,’” Maloney said. “Meanwhile, you’ve got a top-level coach that’s not terribly interested in rebooting a team. He’s coaching to win games right now because that’s his job, but when you go back and look at the year or two after we had that run to the semifinals, at the decision to maintain instead of rebuild and at the players we signed who didn’t work out, it all added up with us going back to mediocrity or worse.”

During his nine years as the Coyotes GM, Maloney operated on a tight budget that forced him to make several hard decisions. For example, he had only had one, part-time scout covering all of Europe during league ownership, which basically meant relying on NHL Central Scouting or giving up on European prospects. Nonetheless, Maloney shakes his head when pondering some of his moves.

“I do feel some responsibility for where this team is at now,” he said. “As a manager of a team, you’re hired to put a winning product on the ice. I’m 100 percent convinced that if you put a winning product on the ice it’s going to get support. You can make excuses about the challenges, but that’s the job. We just didn’t win enough. We didn’t get to the playoffs enough. We didn’t win playoff rounds and it just keeps perpetuating this negativity that surrounds this franchise.

“If I looked at my time here and you asked me, ‘What was the biggest regret?’ It was our drafting and development. If you don’t draft well you don’t have the assets to get better and use better. I don’t care what the payroll was. I should have demanded more. I should have been more forceful, to be honest with you, to say, ‘This franchise can’t prosper unless you draft properly and develop.’ Our development department was basically nobody and the drafting was a challenge because of a lack of resources in scouting, but if you’re drafting in the first round, especially in the top 10, you have to hit on players. You have to get top-six forwards or better. We didn’t do that.”

End of an era

When Alex Meruelo officially purchased the team on Aug. 1, 2019, becoming the first majority Latino owner in league history, there was widespread hope that the Coyotes had finally found a deep-pocketed owner. Meruelo arrived with a net worth estimated in the billions and little bravado other than his energizing “I sure as shit want to win” line at his introductory news conference.

At the same time, Meruelo wasn’t shy about noting the team’s tenuous situation in Glendale.

“My focus right now, with the rest of my team, is to get something that is financially sustainable in Arizona,” said Meruelo, who purchased a 95-percent stake in the team with Barroway retaining the other 5 percent. “It’s a difficult situation. We lose quite a bit of money here. It’s difficult because our fan base is more in the (East) Valley, it’s not out here. The corporate sponsors aren’t really out here. We don’t have a long-term lease. All of those are really big challenges that I have to address and we have to address as a team, but I am committed to making it work, whether it be here or someplace in the Valley. I want to be part of this state. That is my sole interest.”

A global pandemic that wreaked havoc on Meruelo’s businesses, and a series of controversies in the ensuing three years have eroded some of the initial confidence in his ability to rescue the Coyotes. Included in those was a messy breakup with GM John Chayka, a scathing report from The Athletic on the internal workings of the organization, and a trail of unpaid bills to vendors, players and the City of Glendale.

The latter, coupled with the team’s pursuit of a permanent home in Tempe finally brought to a close a relationship with Glendale that has been dysfunctional for more than a decade. Long-time supporters of the franchise hope that doesn’t also mean an end of the Coyotes era in Arizona. The team and league remain hopeful that an arena solution can be found.

“Just because there are challenges doesn’t mean you throw up your hands and walk away,” Bettman said last summer. “The goal is to meet the challenges and overcome them.

No one has done more to keep hockey in the Valley than Bettman, but he shrugs off criticism that characterizes him as stubborn in the face of an impossible situation.

“At the end of the day, the criticism is generally more pronounced than the reality and that’s been the case here,” he said. “The criticism generally came from places that didn’t have a franchise and would like one. We stand by all of our communities and we do everything in our power not to relocate.

“There was criticism in a couple places where we couldn’t make it work and ended up moving, including one of which resulted in the team in Arizona, so you get criticized when you stand by your franchises and don’t allow a move and you get criticized when you move them. To me, it’s not about the criticism. It’s really about making sure we’re trying to do the right things. I am comfortable that in the course of the last 25 years, we and the ownership groups for the most part have tried to do what they thought was right.”

While Bettman has been steadfast in his support of the Coyotes, he did show a hint of weariness when asked at the NHL All-Star Game in Las Vegas about the Coyotes’ ongoing pursuit of an arena in Tempe; a pursuit whose resolution date is still unknown.

“It’s something that has to be done in the short term,” he said. “It’s not gonna be two weeks but it’s not gonna be two years. If there’s no prospect of a new building then we’re going to have to focus with ownership on what makes sense, but as long as there is a realistic possibility in the near term of a new arena in the right place, we think there’s a tremendous opportunity in that vibrant market.”

Wherever the Coyotes end up, it appears that their Glendale chapter has closed for good.

“It will be strange not going back there,” said Doan, now the Coyotes Chief Hockey Development Officer. “It has been home for my family and for me and for all my friends and extended family for a long time, and you don’t get to work in the same spot for 19 years too often.

“I go in there every day for work and I walk in through Westgate. It’s a great spot. The building is a great place to watch a game. They did an incredible job of designing it and laying it out and the City of Glendale should be really proud of it.”

As Johnson walked into the arena for the last time to work a game between the Maple Leafs and Coyotes on Jan. 12, he adopted a wistful tone.

“I got kind of nostalgic driving out to Glendale, thinking that this is it,” he said. “Arizona was good to me. Even if we didn’t have a ton of team success, personally, I had my best career years there, my kids were born there, and it’s the place I played the longest so it kind of felt like home.

“For me, it’s disheartening that a market that I think is better than it is perceived, and a market that has a chance to be way more successful than it has been just gets another kick in the teeth, another knock saying, ‘See, it doesn’t work. They don’t like hockey there. It doesn’t make sense,’ and on and on and on.

“I don’t think that’s the case. I feel like if things had been done differently, it wouldn’t have been like this, but it just feels like a lost two decades. There were some good moments and some good intentions and I’m not saying it was on purpose, but an organization spent two decades spinning their tires, going nowhere. That’s too bad because that’s two decades where growth and support and economic development and all those different things could and should have been occurring.”

Follow Craig Morgan on Twitter

Comments

Share your thoughts

Join the conversation