© 2026 ALLCITY Network Inc.

All rights reserved.

For 23 of the Coyotes’ 26 seasons in the Valley, arena location has been a crippling handicap to their financial and on-ice success. On Tuesday, the Coyotes may finally put those struggles to rest.

In a special election for propositions 301, 302 and 303, Tempe voters will decide the fate of the Coyotes’ proposed arena and entertainment district along the south bank of the Salt River. A simple majority yes-vote on all three propositions would grant the Coyotes license to clean up what is now a dump site at the northeast corner of Priest Drive and Rio Salado Parkway.

There is still pending legal action taken by the City of Phoenix against the City of Tempe, as well as a countersuit, but there is nothing currently in place that could prevent the Coyotes from breaking ground on a new home that sits at the core of the Phoenix metro area. The proposed location is mere blocks from Arizona State University, three miles from Sky Harbor International Airport, seven miles from Old Town Scottsdale and 10 miles from downtown Phoenix.

The location also sits at the core of the Coyotes’ premium season ticket holder base, at the core of the city’s wealth and population base, and within the corridor of corporate bases, stretching from north Scottsdale, through Phoenix and Tempe, down to Chandler along the 101 freeway.

“It puts us on the same playing field with everyone else,” said Coyotes icon and executive Shane Doan, who has a greater perspective on the franchise’s arena saga than anybody on the planet because he has been here for every year of it. “The Valley is event based. This is an event-based building that’s going to create events and give us the opportunity to put a winner on the ice that has been hard to do with everything that has gone on.”

The Coyotes have not treated their fans to enough on-ice success in their 26 seasons in Arizona. The team has made the playoffs nine times in that tenure and it has won just four postseason series. But it’s a chicken-and-egg scenario. The team has had seven majority owners, preventing the sort of stability that filters down to all other aspects of the franchise. And it has never had the right location, save for those initial three seasons when fans turned out in big numbers and there was excitement surrounding the Valley’s newest entertainment option.

Before Tempe decides the Coyotes’ fate with vote results that should become public starting at 8 p.m. on Tuesday, here’s a look back at the Coyotes’ arena saga, which encompasses the entire 21st century.

America West Arena

Excerpts of this section first appeared in a story that I wrote on July 1, 2021 to mark 25 years of Coyotes hockey in the Valley.

America West Arena was a unique venue for NHL hockey. Because it was built solely for the Suns, it was (and is) small, intimate, loud and ill-designed for a 200-feet by 85-feet ice sheet. The north end of the arena could not accommodate anything more than makeshift metal bleachers under the first balcony, and that balcony hung right to the edge of the glass at the north end, preventing anyone but the first row of fans from seeing the goal below them.

To alleviate the latter problem, the team hung a large screen from the rafters so that fans in the balconies could see the action in the north zone. In those days — before Brittanie Cecil died when a puck struck her in the left temple at Nationwide Arena in Columbus, Ohio, on March 16, 2002 — there were no nets attached to the top of the glass to protect fans. It was especially notable in that north end because of its proximity to the ice surface.

Despite the challenges, the players enjoyed playing in the atmosphere-charged arena.

“Those first few years at America West Arena, that place was rocking,” former Coyote Keith Tkachuk said. “Everybody talks about the Coyotes attendance problems now, but when we were downtown, that wasn’t a problem. The place was packed, it was loud and it was a lot of fun to play there.”

Unfortunately for the Coyotes, their new home became untenable after just three seasons due to rising payrolls, the inability to maximize revenue as a Suns tenant, and an arena configuration that forced the team to discount seat prices at the north end.

“When I bought the team, the average league salary was $17 million; when I sold it, it was $44 million,” former owner Richard Burke said via text message. “Our breakeven at America West Arena was $29 million, which we exceeded after three years.

“Hockey was and is an arena sport. Most of your revenue comes from what happens in your building; not like other major sports from television, radio, etc. It is tickets (the high-end ones), suites, concessions, building naming rights, sponsorships, et al. After the 1997-98 season we saw the handwriting on the proverbial wall. Superstar salaries started to balloon. Keith Tkachuk got $7 million per year and I let our goalie [Nikolai Khabibulin] sit [in a contract dispute] for 1½ years.”

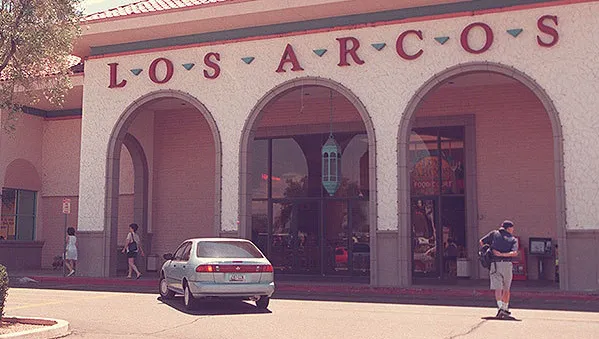

Los Arcos

Burke thought that the site of the old Los Arcos Mall in south Scottsdale would be the perfect footprint for a new arena that could provide the team with the additional revenue to survive. It was close to the vast majority of the team’s premium season-ticket holders, and it was close to the airport, Old Town Scottsdale and Arizona State University.

Everything looked like it was on track for completion. The team even held a groundbreaking ceremony in 1999 for which Doan still has the shovel.

Despite initial voter and city council approval, however, the Scottsdale deal remained in limbo and property owner Steve Ellman was mulling an offer from the City of Glendale, whose mayor, Elaine Scruggs, wanted to make a name for the city in what everyone thought was the next big growth area of the booming Valley. Eventually, Burke gave in to pressure and sold the team to Ellman.

“We had a pretty complete deal to build a new stadium at Los Arcos. The stadium deal was there. The state and local tax revenue were there and I was prepared to put up the difference,” Burke said. “The piece of property was owned by someone else and it came down to the fact that those people wanted to own the team as well as build the building. In the interest of getting it done, I put it straightforwardly: ‘Either you sell me the land or I’ll sell you the team but we have to put the two together so we can get this done.’

“It’s too bad with hindsight. If it had stayed on the east side, I guess we’d probably still own the team but going where it did, it was not in the cards. I was forthright with them in saying that my personal opinion was I didn’t think it would work out there. You need to stay over here. It didn’t happen and I think all that followed was just a consequence of the economics because it wasn’t working financially. It created ownership instability regularly because of the losses in trying to find someone capable of handling those losses at the magnitude they were. A followed B.”

Glendale/Jobing.com/Gila River Arena

It’s impossible to say what might have happened in Glendale had the 2004-05 lockout not stalled the Coyotes’ momentum one season after moving. It’s impossible to say how much different the season ticket base might look if the Great Recession hadn’t stalled all of that expected growth in the West Valley. Twenty years later, however, it is undeniable that the West Valley, Glendale and the footprint at Westgate City Center look a lot different than the initial projections.

“I remember Ellman telling people at one point that if you looked at where the population center of the Valley would be between how many people would live north and south and east and west, it was going to be somewhere right around where the arena and the Westgate development were,” said Jeff Hecht, who was director of public affairs for the Ellman Companies until 2008. “But just because people moved there didn’t make it any closer for the people in Mesa or Tempe or Chandler or Scottsdale; those loyal season-ticket holders who had supported the team when it was in downtown Phoenix and now had to drive all those extra miles. It just meant that they were really going to try to attract people from the west side and when it opened there would be a huge population center to pull from, west of the arena.

“It never developed out on the level that it was expected to and if you look at Westgate to this day, it looks very similar to what it looked like when it opened in 2007 with the exception of a few other parcels like that outlet mall they built along the freeway. The initial plans called for far more. All the parking on either the east or the west side of that main center core of Westgate was all supposed to be developed out. It was all planned to be city blocks of residential or retail or different types of entertainment or little pocket parks and none of that stuff ever really came to be as it was planned.”

Over the years, the relationship between the city and the Coyotes soured to the point where you could only describe it as toxic. First, unwitting owner Jerry Moyes tried to put the team in bankruptcy and sell it to Canadian billionaire Jim Balsillie to move it to Hamilton, Canada. The league blocked that move and won its case in court, eventually taking over control of the team until it sold to the IceArizona group in 2013.

The league and the new ownership group thought they had secured the franchise’s future in Glendale when the city agreed to a 15-year, $225 million arena-lease agreement, but the city ripped up that agreement two years later, citing a questionable conflict of interest with two employees. It was soon after that breach of a business relationship that commissioner Gary Bettman vowed the Coyotes “cannot and will not remain in Glendale.”

The team and city eventually agreed to a year-to-year lease agreement which the city infamously ended in the summer of 2021 when the Coyotes refused to sign a long-term lease and Glendale discovered that the team was courting Tempe as a potential new site. In nearly two decades in Glendale, the Coyotes never turned a profit and often lost tens of millions of dollars per season.

Homeless

Faced with the prospect of being homeless, the Coyotes explored multiple venues in the Valley to try to find a temporary solution, but everyone one of those had a litany of issues. Former Suns owner Robert Sarver wanted no part of the Coyotes at what became Footprint Center, and had the Coyotes moved back into their former home, they would have suffered the same financial issues that forced them to leave.

The team considered Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum, but president and CEO Xavier A. Gutierrez said the cost to renovate the 55-year-old facility was astronomical and it has no suites. The franchise also considered Chase Field, home of the Arizona Diamondbacks, but there were too many logistical issues including available dates.

The Coyotes finally settled on ASU’s 5,000-seat Mullett Arena which will be their home for a full four seasons assuming everything goes according to plan — and despite its obvious financial shortcomings. The Coyotes chose the venue in part because it is in Tempe where they hope to forge a long-term relationship with the city and ASU, the city’s largest employer and most influential tenant.

This isn’t the first time that the franchise has explored a location near ASU. The Coyotes have known for a while that the location made sense for all of the aforementioned reasons. This is the first time, however, that a deal has made it to the very edge of success. With a favorable Tempe vote on Tuesday, the Coyotes may finally cross the finish line.

Top: Artist rendering of the Tempe Entertainment District via Arizona Coyotes

Follow Craig Morgan on Twitter

Comments

Share your thoughts

Join the conversation